Climate Canary

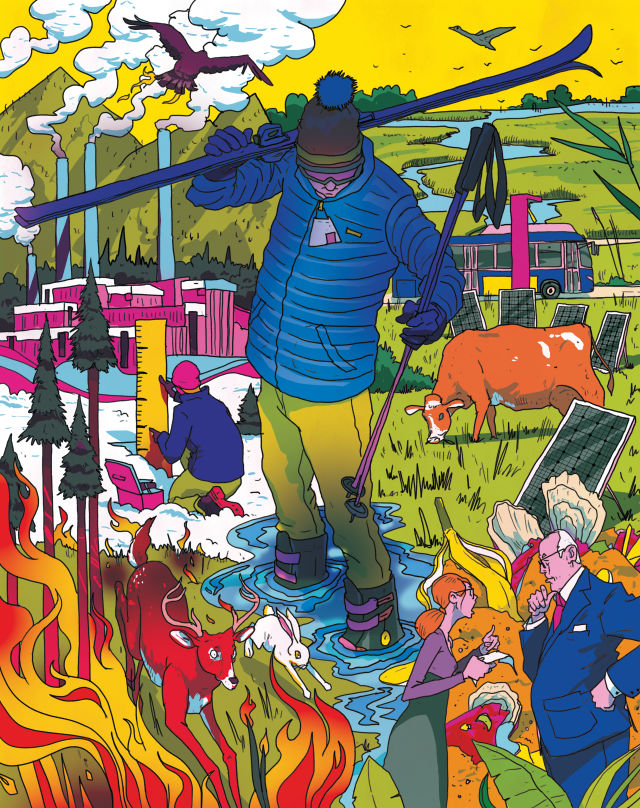

Since the 1970s, Park City has lost roughly six weeks of wintertime temperatures. The absence of those critical weeks has impacts that are tough to overstate: a shortened ski season; less snowpack; less water; agricultural challenges; heightened wildfire danger; and a host of anticipated meteorological, economic, and societal effects on the horizon.

The change hasn’t gone unnoticed. Back in 2006, forward-thinking locals put together a Save Our Snow study and summit, drawing attention to dwindling snow levels as well as to big-picture climate woes. As the Paris Climate Accord was heating up, Park City got serious, setting sustainability as one of its critical priorities, with a community goal of producing [or emitting] net zero carbon by 2032. Then, in light of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2018 report marking 2030 the do-or-die deadline for curtailing greenhouse gas emissions (and with a potential Olympic Games on the horizon), the timeline changed—and Park City set one of the most ambitious climate-related goals in the world.

The goals are in place: net-zero carbon emissions and 100 percent renewable electricity by 2022 for the city, and by 2030 for the community at large, with similar (but carbon emissions–based) goals set by the county. There’s buy-in from local corporate interests, and an MT (Mountain Towns) 2030 movement has sprung up. The upshot? Historically conservative Utah is marching a progressive—and, at times, surprising—path to placating Mother Nature. And this little ski town is pioneering and collaborating across borders in the battle to mitigate climate change.

“If we can convene and develop these larger partnerships, we’re going to at least change the West and show a pathway forward for North America, if not the world.”

—Luke Cartin, City Sustainability Director

Green Goals

Park City Municipal’s goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2022 means weaning city operations (a $25 million spend annually, spanning everything from the electrical lights in the library to fuel for the snowplow fleet) off of all fossil fuel–based sources within two years. The community-wide goal of net zero by 2030 means tackling a current $245 million spend on traditional fossil fuels, a number that takes into account use by all businesses and residents, plus “externalities” such as imported goods, services, a commuting workforce, and ski resort guests (think airline travel).

City Sustainability Director Luke Cartin explains that the plan is to shift that $245 million spend from fossil fuel providers around the globe to Utah-based (and regional) renewable energy providers. “We want to use renewables, which de-risk [eliminating exposure to fuel price fluctuations], create jobs, and so forth,” he says. “Think of that economic impact: if we can take that $245 million and capture even 20 percent of that within our greater community, that would be almost a $50 million spend that would stay in our economy.... That’s a big benefit for the state of Utah.”

Like the city, Summit County plans to transition to using 100 percent renewable electrical energy for county operations—and make renewable energy available countywide—by 2030. However, in lieu of a net-zero framework, the county has taken a slightly different approach by adopting goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of county operations to 80 percent below the 2016 level by 2040 and 80 percent below the 2014 level countywide by 2050. In other words, the county aims to make an impact “by taking actions to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels associated with greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution,” according to county Sustainability Manager Lisa Yoder.

On the nongovernmental side of the equation, local resorts, businesses, and mountain towns around the country are aligning net-zero 2030 goals, in part thanks to the Park City–born MT 2030 Summit (mt2030.org, see “Inspiring Others,” p. 72).

The Road Map

Since this is uncharted territory, no one has a precise road map to reduce their CO2 impact in our warming world. In this rapidly changing realm, the current consensus seems to focus on four key aspects, at least here in the Wasatch: shifting to renewable sources (and embracing electrification), reducing consumption, reducing waste, and promoting regenerative agriculture.

Shifting to Renewable Sources

For all local players, securing renewables ranks high on the to-do list. Park City’s Cartin likes to point out the fact that Utah’s state rock is coal, yet Utah is forging a new path to renewables—without taking the carbon credits route (in which fossil-fuel usage is offset by funding wind, solar, or other innovative energy sources somewhere else in the world).

Locally, the coup-de-decade on the climate-change front is a budding public-private partnership that transitions a substantial chunk of electrical usage from fossil fuel sources to homegrown solar. Six entities—Park City Municipal, Summit County, Salt Lake City, Park City Mountain, Deer Valley Resort, and Utah Valley University—have teamed up with the existing utility, Rocky Mountain Power, to build a roughly 100-acre solar farm near Tooele, which is designed to meet 100 percent of the participating entities’ electricity demands. The project is anticipated to be online by the end of 2022.

For the community aspect of the net-zero objective, a similar, but larger-scale, bulk-buy model with the utility will pave the way for more renewable sources in the state. So far, 23 Utah communities have agreed to the goal of 100 percent renewables by 2030. The pathway forward is being framed, along with a slew of regulations, off-ramps (should communities need to bail out), and an opt-out (rather than an opt-in) choice for individual residents and businesses. Negotiations are under way.

This type of public-private partnership—both the six-entity solar buy-in and the burgeoning 23-community model—is possible thanks to the 2019 passage of the remarkably progressive House Bill 411, the Utah Community Renewable Energy Act. Rather than set communities in opposition with their utility (e.g., prompting a divorce between the local utility and its cities, as has happened in Boulder, Colorado), the Act set the stage for an investor-owned utility to provide opt-out renewable energy options.

“If Park City went carbon neutral tomorrow, it wouldn’t affect anything,” says Cartin. “But if we can convene and develop these larger partnerships, we’re going to at least change the West and show a pathway forward for North America, if not the world.”

Reducing Consumption

Purchasing renewables and reducing energy needs (such as adding insulation and replacing old lightbulbs with LEDs) are the low-hanging fruit. According to Lisa Yoder, buying renewable power will reduce Summit County’s impact by 20 to 30 percent. “That’s the big, easy step,” she says. “And it wasn’t easy. It’s been in the works for five years. Especially difficult was the community-wide aspect.”

Reducing consumption (and pollution) is an obvious—albeit more challenging—next step. “We need to be more mindful and less wasteful,” says Yoder. The county is buttoning up its buildings and facilities (increasing efficiency in heating, ventilating, lighting, and such), adding rooftop solar where appropriate, and replacing its vehicles with hybrid/electric vehicles as its current vehicles need replacing, with a goal of transitioning at least 50 percent of its fleet by 2022. Both the county and the city are increasing the numbers of publicly available EV charging ports and adding to the shared electric bike fleet, and their innovative, two-year-old electric bus initiative is serving as a model for communities around the country. Plus, in an effort to stave off pollution and inversion, no-idling ordinances are in effect.

Reducing Waste

In terms of reducing waste, private businesses—both mom-and-pop shops and large corporations—are leading the charge (though both the city and the county are talking trash, too).

Beyond recycling office paper and eliminating straws, small businesses are getting creative when it comes to thinking outside of the dumpster. Local catering company Savoury Kitchen nabbed Recycle Utah’s 2019 Green Business of the Year award thanks, in part, to such progressive outside-the-bin thinking. Chef-owner Joseph Saladyga and his staff not only significantly reduced plastic usage, but they also purchased, repaired, and retrofitted an old walk-in freezer, saving it from the landfill while replacing three less-efficient, residential-style freezers. 2018 Zest for Zero (another Recycle Utah award) winner Park City Coffee Roaster ditched its polyester coffee bag liners for rice paper, and the award’s 2019 winner, Este Pizza, committed to composting all of its food waste locally.

Vail Resorts, Alterra Mountain Company, and Powdr—parent companies for Park City Mountain (PCM), Deer Valley Resort (DV), and Woodward Park City, respectively—are all diverting landfill fodder. At PCM, food waste is sent to Wasatch Resource Recovery, a Salt Lake City–based anaerobic digester that transforms garbage into natural gas and nutrient-rich fertilizer. Thanks to “active busing” at PCM’s eateries, the resort has managed to divert 90 percent of food waste (and 65 percent of overall waste), composting 221 tons last year, according to Tom Bradley, Vail Resorts’ regional sustainability manager.

DV and Woodward similarly hand-sort and divert waste, sending their compostable goods, from oyster shells to banana peels, to Wild Harvest Farms in nearby Peoa. DV is diverting roughly 85 percent of its food waste (and 47 percent of overall waste) and last year sent 220 tons to the farm for composting; they hope to “close the loop” on that cycle by bringing back some of those composted soils—along with their microbial properties—to combat noxious weeds on the mountain. All three resorts have shifted to reusables (e.g., no straws or single-use cups and utensils).

Promoting Regenerative Agriculture

The steps beyond reducing waste and consumption and shifting to renewables get even more creative—or elusive—depending on how you want to look at it. For the past two summers, the city has teamed up with Summit Land Conservancy (SLC) and Bill White Farms to implement regenerative agriculture by reintroducing cattle and soil-enhancing plants to city-owned open space flanking the iconic McPolin Barn. Yes, the cows now grazing the lands emit methane, but Cartin argues that the benefits far outweigh the gassiness of the bovines. The cows are carefully managed to act as natural weed killers, lawn mowers, and fertilizers, giving way to biodiversity and healthy soil. This nod to the farm’s agricultural heritage and “living laboratory,” as Cartin refers to it, has layers of eco-benefits, with the most impact potentially coming from the soil itself in the form of carbon sequestration.

“If we can sequester carbon in the soil, it stays in the soil,” explains SLC’s Cheryl Fox, noting that while trees are excellent carbon sinks, they eventually die and release carbon back into the atmosphere. Citing regenerative agriculture studies in California, she says that expanding healthy soil efforts at a larger scale could mean sequestering up to 37 percent of the carbon we’re currently adding to the atmosphere.

“Plus, there’s a cascade of additional benefits, including clean water, biodiversity, and recreational access,” she adds. “We feel like it’s a win-win on a lot of different fronts using open space.” Cartin and Fox explain that the local city–nonprofit effort is taking a scientific approach as the living laboratory moves forward, testing soils and measuring effective approaches to regeneration—and sharing best practices offered by those who know the business best: ranchers and farmers.

And open space—without agriculture or development—plays a vital role in carbon sequestration as well. According to Wendy Fisher of Utah Open Lands (UOL), “Wetlands are one of the greatest carbon sinks”; this “kidney of the landscape” joins forests in “sucking up carbon.” Together, the local land trusts have helped preserve close to 70,000 acres in Utah; UOL reports 62,000 acres to date, and SLC oversees 6,858 acres in 42 conservation easements. Almost three-quarters of the land within Park City limits comprises open space, hence planting the roots—literally—for carbon sequestration.

Given the tens of millions of dollars public and private entities have poured into purchasing swaths of land over recent years, it’s clear that Park City loves its open space. But it took what Park City Mayor Andy Beerman calls “a carbon army”—a group of young Parkites rallying for the environment and consistently showing up at town meetings—for city council to move beyond enthusiasm for hiking and mountain bike trails to big-picture sustainability goals. And a few of those activists recently took that message beyond city hall, hoping to rally similarly minded communities to the net-zero-by-2030 goal.

Inspiring Others

Spearheaded by Luke Cartin, Andy Beerman, and a few of those activist-citizens (primarily event co-chairs Bryn Carey and Eyee Hsu)—and with the help of nonprofit Park City Community Foundation—October 2019’s MT 2030 brought together mountain-town governments, businesses, nonprofits, and experts to share best practices and a commitment to a 2030 net-zero emissions goal. The three-day event challenged community leaders from resort towns and counties to jump aboard the 2030 commitment train as panels, breakout sessions, and field trips helped illustrate both the challenges and the solutions. The event also reached out to the general public via an inspiring evening with Dr. Jane Goodall and Project Drawdown’s Paul Hawken.

“Everyone wants to contribute and be a part of the solution. But they don’t know how to actually do that,” says Carey. So MT 2030 brought the players together, urged them to set bold goals, and is now helping facilitate road maps to get there.

“There’s a cocktail of approaches that can be deployed in any particular way,” explains Richard Bezemer, who coordinated the conference and serves as MT 2030’s integrator. “[MT 2030] exists to help make the action happen faster, better—with less risk and less cost—and with a quicker result than would otherwise happen if we didn’t exist. We’re an accelerant.” The solutions spread and scale faster, he adds, through participants’ shared knowledge of experiences and successes.

Some of the MT 2030 ripple effect is that momentum toward shared practices—even among competitors like ski resort operators Boyne, Vail Resorts, Alterra, and Powdr. In October, four executives from these industry rivals stood up on stage and agreed to essentially open up their best practices to one another. Cities and corporate leaders offered to share their experiences and RFPs regarding everything from electrification of bus fleets to reduction of waste. As Bezemer puts it, the synergy is more about comfort than collaboration, a sense that “if you can do this, we can do this.”

“We are talking about mountain towns, but that’s just the start,” Bryn Carey explains. “The goal is that the state of Utah can do this. And if the state of Utah can do this, why can’t the western United States do this, and if the western United States can do this, why can’t the country do this?”

MT 2030’s bold goal-setting agenda, which includes actions and influence components, continues to evolve—both organically and in a formal setting with the second annual conference slated for Breckenridge, Colorado, this fall.

How It’s Going, and What’s Next

On the MT 2030 side of the equation, 44 communities and organizations (and counting), from Moab to Missoula, have committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2030. Plus, Park City Community Foundation (MT 2030’s fiscal sponsor) announced a Park City Climate Fund (PCCF) with the goal of boosting innovative homegrown ideas. The inaugural recipients, TreeUtah, Utah Clean Energy, and Recycle Utah, are just getting started on their respective projects—community events to plant trees that in turn sequester carbon in the soil; facilitation of the community’s carbon-neutral electricity supply and prioritization of climate strategies in the building sector; and a community education program to promote reaching zero waste by 2030, respectively. Park City High School’s Earth Club also received more modest funding toward its projects, ranging from composting to promoting carpooling.

“With climate change, you really need to localize your solutions, but you also hope that they can have an impact outside of your locality,” explains PCCF Executive Director Katie Wright. Time will tell whether these nonprofits will be in the position to pass along their successes to other communities. The next round of grants will be chosen in the fall.

As for the government entities, “We’re on pace, and we’re moving with appropriate urgency and conviction,” says Beerman.

Thanks to the utility partnership and HB 411, Park City and Summit County are on track to meet their 100 percent renewable goal. As far as emissions go, Yoder reports that county operations emissions went up 10 percent last year due to the increased number of buses in the transit fleet, but as renewable energy comes online that should go back down. “Had we not been doing all that we had done, those emissions would have increased by 24 percent,” she says. Growth, too, is a mitigating factor.

Both the city and county are now turning their attention to heating, sorting out ways to partner with natural gas provider Dominion Energy—tossing about ideas like biogas captured via landfill emissions. And speaking of landfills, the city recently announced a zero-waste commitment; the county is also eyeing ways to reduce trash as the Three Mile Canyon Landfill nears capacity. From there, the road map funnels down to the individual level and exploring cleaner ways to eat and consume, circular economy models, and transportation.

“One thing [Mother Nature] is really good at is regeneration,” says Beerman. “If we can back off long enough for systems to regenerate, we’ll have a chance.”

State of the Climate

“Scientific evidence for warming of the climate system is unequivocal,” according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). NASA (climate.nasa.gov) spells out that grim evidence: global temperature rise (1.62 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 19th century—“a change driven largely by increased carbon dioxide and other human-made emissions”), warming oceans, shrinking ice sheets, glacial retreat worldwide, sea-level rise, extreme weather events, and ocean acidification.

Fully 97 percent of climate scientists agree that the cause is human-made greenhouse gas buildup. For millennia, CO2 levels in the atmosphere hovered between 180 parts per million (ppm) and 280 ppm, but since the Industrial Revolution, that number has skyrocketed to 416 ppm. That carbon accumulation results in a bunch of destructive feedback loops, from defrosting Arctic swaths to melting ice caps (no longer reflecting solar radiation).

Of course, the climate fallout of this warming trend has global implications. But what does climate change mean for Park City? According to 30-year senior hydrologist with the National Weather Service Brian McInerney, the ski industry as we know it is likely to “go away” between 2035 and 2065. Already, traditionally snowy months November and March are delivering rain in lieu of snow.

“Research shows that areas that are currently 100 percent snow-covered in December, January, and February are going to be 50 percent or less [15 to 45 years from now],” he says, adding that “by 2100 [with a projected warming of 10 degrees Fahrenheit locally], 80 percent of the snowpack in the western US is going to be gone.” Warm temps mean an inability to make snow, and a high-pressure system (triggered by a rapidly warming Arctic) will likely “park over the West,” leading to drier patterns—for a while. Weather events, when they strike, will come in less-frequent, more-intense deluges. Depleted snowpack means inefficient water storage, and the ripple effects, of course, are global in scale.

The upshot is urgency. According to McInerney, “We have roughly 12 years to turn this around, and then we have runaway climate change.”

Ain’t No Mountain High Enough: Ski resorts step up eco-efforts.

“The sustainability world is certainly not a direct climb up a wall—it’s much more of a bouldering problem—and we are figuring this out together,” says Laura Schaffer of Powdr Corp, who heads up sustainability for the company and presented at MT 2030. Powdr’s local history of environmentalism harkens back to founder John Cumming’s commissioning of a “Save Our Snow” study in 2006 (the first-ever study of global warming’s impacts on Park City’s snowpack and economy), when Powdr operated Park City Mountain Resort as part of its nationwide portfolio. For the following decade, the company focused on energy efficiency and tapping into renewables.

In doing so, Powdr reduced its carbon footprint by 49 percent. But, as Schaffer quotes Cumming, “the hardest 51 percent is yet to come.” Last year, the company performed a comprehensive greenhouse gas inventory and is moving forward with a climate action plan. Locally, Woodward Park City, which opened in December 2019, has a goal of operating its chairlift-served, action-sports-filled 125 acres (and new 66,000-square-foot facility) at the same levels as its previous, relatively petite Gorgoza Park tubing hill. Thanks to its ground-up build, Woodward efficiencies like the living roof and low-flow faucets were “no brainers.” The companywide hope is that its site-specific climate solutions (from solar at Boreal to cow manure–fueled power at Killington) and “Play Forever” program and mantra help inspire all stakeholders to work toward solutions—and share successes.

Vail Resorts, parent company to Park City Mountain, has committed to not only net-zero emissions by 2030, but also zero waste to landfill and zero impact on forest and habitat by the same deadline. Vail has taken various steps across its three dozen resorts, from purchasing wind and solar to the Park City location’s waste reduction by shipping off food waste to the anaerobic digestor in Salt Lake City. Eco-accoutrements, such as solar panels and EV charging stations at PCM, are part of the solution—as are behind-the-scenes actions, like adding snowmelt controls to roofs and concrete plazas.

“Zero waste will always be the biggest challenge,” explains Tom Bradley, Vail Resorts’ regional sustainability manager. Like Powdr, Vail is rallying employee passion and hoping to influence resort guests, while tracking and adjusting road maps as it tackles its bold commitments. So far, thanks to regular audits, Bradley says the company is on track, and that the goals are attainable.

Eco efforts at Deer Valley Resort have been a quiet, but significant, part of the company’s fabric for decades, with department heads like former food and beverage head Julie Wilson (and now Jodie Rogers) and Maintenance’s Jonathan Hughes and Trevor Peterson implementing improvements in a grassroots manner. Think e-snow guns, HVAC efficiencies, sustainably sourced ingredients, tier 4 diesel snow cats, landfill diversion, and employee rideshare promotions—as well as the more obvious “Clean the World” lodging products and carpooling lot at DV. “We’ve been trying to do a lot of these things for a long time; we just never talked about it,” says Sustainability Manager Julie Schultz.

Like PCM, DV is signed on to the 100 percent renewable by 2022 plan through the Rocky Mountain Power–city–private partnership. As of fall 2019, the company has an official sustainability department headed up by Schultz, who’s been a longtime unofficial eco ambassador. On the corporate level, Alterra is adding an umbrella element to the movement with a newly appointed VP of sustainability, former COO David Perry, who Schultz says will bring an element of activism to the climate-change battle. “We’re a business and we’re a ski resort, but we have a big voice.”

Pitch in for the Planet

Though big corporate and government efforts are vital to mitigating climate change, individuals can make a difference, too. Here are a few local resources to get some ideas and make a start:

- Check out workshops (composting, perhaps?), resources, and tips at Recycle Utah, a local nonprofit that is about much more than recycling—but they can help you with that, too. Of note: For those unwilling to schlep bottles to the nonprofit center, Momentum Recycling offers curbside glass pickup service.

- Take Utah Clean Energy’s Summit Community Power Works Challenge, an education-action tool that steers you through steps (little and/or big) toward making an environmentally friendly (and potentially cost-saving) impact.

- Join Swaner Preserve and EcoCenter for a range of green activities, from volunteer restoration efforts and earth-friendly workshops to kids’ camps and nature walks and lectures, or simply peruse the exhibits for eco-building ideas and a glimpse into local habitat and wildlife.

- Explore open space with (or without) one of wesaveland.org Summit Land Conservancy’s Hops Hunters hikes and Moon Shine snowshoes or programs introducing kids to nature and free play. Similarly, Utah Open Lands (utahopenlands.org) has land-inspired events and space to roam. Trail maps are available via Mountain Trails Foundation.

- Invest in a home composter (available for purchase via Recycle Utah) or use a curbside pickup service, such as Spoil to Soil.

- Unleash your innovative idea with a grant application to Park City Community Foundation’s Climate Fund.

- Plant a garden or a tree via Summit Community Gardens or TreeUtah.

- For big-picture resources, dive into Project Drawdown’s solutions, from shifting toward plant-rich diets to wetland restoration.

Spotlight on Solar

Utah has oodles of sunshine, but the relationship between solar and Rocky Mountain Power is a bit complicated. On the one hand, the utility is locking arms with public and private entities to build solar farms and supply renewables via the grid. On the other hand, the utility is locked in a battle with solar proponents over rooftop solar credits.

“If they get to own and operate massive amounts of renewables ... they win, we all win,” says county Sustainability Manager Lisa Yoder. “With rooftop solar, the utility loses. They’re not providing the source.”

Currently, the county is in its third round of a communitywide, bulk purchase (i.e., discounted) rooftop solar program via scpwsolar.org. Of note: this fall, Rocky Mountain Power is proposing a change (a significant reduction) to the net meter rate. So if rooftop solar is on that to-do list, get into the queue now.