Ever Wonder What Park City Will Look Like 20 Years From Now? Here's a Forecast for the Future.

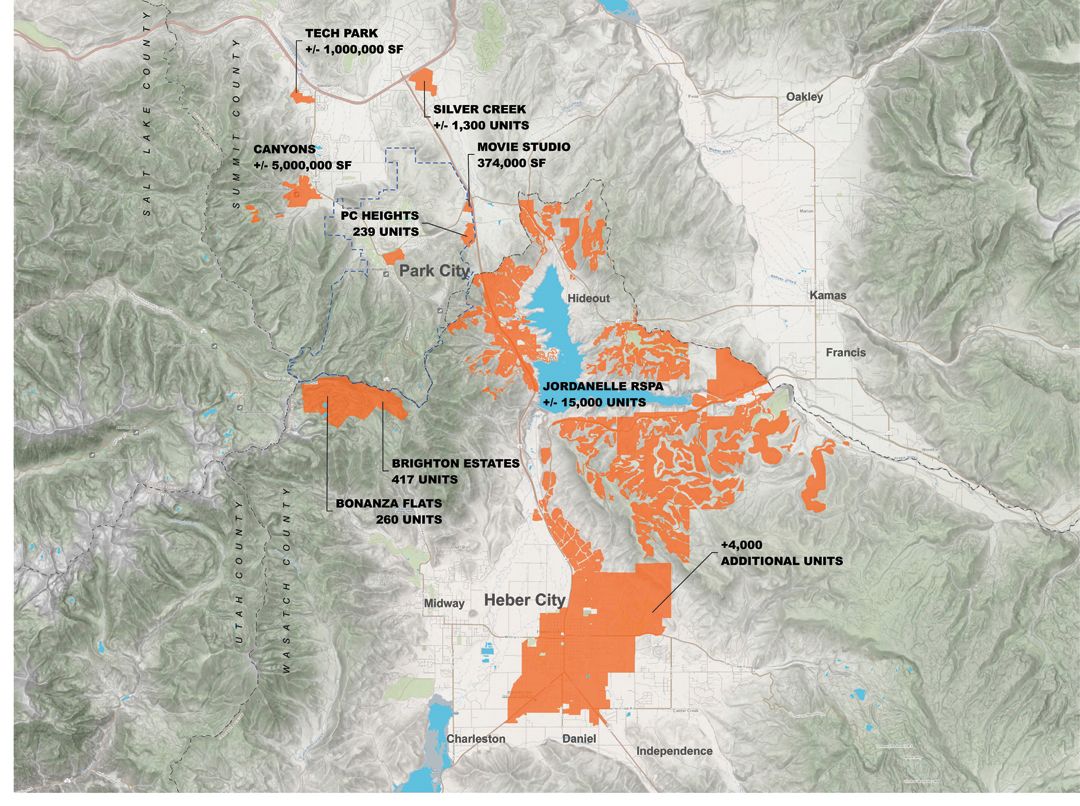

The orange shaded areas indicate current zoning densities. Please note that units shown may not have received all development approvals from all required agencies and governments. No representation of development rights are projected or inferred.

No one expected this town, incorporated in 1884 as a silver-mining outpost, to survive 50 years, let alone another century on top of that. Yet, in its evolution from boomtown to busted backwater to resort destination with 600,000 annual visitors, Park City has somehow managed to cling to a rare everyone-knows-your-name persona. Now, however, on the verge of yet another boom, many in the community are concerned about how Park City may look and feel in the future.

Adam Strachan was a young teen with dreams of being an Olympic skier when he moved to Park City from Salt Lake City with his parents in the 1980s. Now a 40-year-old lawyer and dad, he rides his bike to work nearly every day from his home in the Prospector neighborhood. Strachan believes in giving back to his community and, along with giving his time to local nonprofits like the Mountain Trails Foundation, has been on the Park City Planning Commission for more than eight years, the last two of which he has served as chairman. As much as he loves his adopted hometown, however, he’s pessimistic about its long-term forecast. “You’re not going to have a small resort ski town anymore,” he says. “We are losing our community fabric.”

The decline of affordable housing—which began with the steep rise in real-estate values after the 2002 Olympic Winter Games and resumed with a vengeance after the Great Recession—is, in part, what Strachan and others blame for the present identity crisis. According to the Park City Board of Realtors 2016 Second Quarter Statistics report, property values have increased at approximately 7 percent annually since 2012. And over the last year, the median price of a single-family home within the city limits has increased by a whopping 19 percent. As a result, many of Park City’s professional and service staff have moved to places like Heber City, Oakley, and Kamas. More than half of the 10,000 jobs located within Park City limits are filled by people living outside of town. This mostly commuter workforce is a major contributor to traffic congestion—particularly during the busy winter tourist season.

And Park City’s neighboring communities are becoming less affordable, too. “Over the last 12 months, the trend of buyers searching for value continued as the Heber Valley experienced double-digit growth in the number of unit sales, dollar volume, and median price,” notes Rick Shand, Park City Board of Realtors president, in the Q2 report. In fact, the 22,000 acres surrounding the nearby Jordanelle Reservoir are zoned for 13,000 units. Thanks to its proximity to the private airport in Heber, as well as Deer Valley’s Jordanelle Gondola, developers have luxury condos on their minds, not middle-income housing.

The high demand for Park City–area real estate is also chipping away at our once taken-for-granted open spaces. Twenty years ago, Snyderville Basin, which extends from the McPolin Barn on Highway 224 to Kimball Junction, was mostly farm fields and sagebrush. But from 2000 to 2010, its population rose from 3,636 to close to 22,000, according to census estimates. And if growth projections made by the Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget are accurate—Summit County population growth through the year 2020 will be nearly double the state average of 2.2 percent—migration to this once development-free buffer between Park City and Interstate 80 will continue.

The 28-unit Richer Place Apartments in Kimball Junction

Summit Land Conservancy’s Cheryl Fox is concerned that the current pace of development will affect precious resources like water quality. Her group is working to save the Weber River, which provides drinking water to a third of those living on the Wasatch Front. Fox says that large-scale and largely unregulated development “degrades the water quality, limits public fishing access, removes prime soil from agriculture, and puts homes in the path of weather disasters.”

The seriousness of these and other growth-based challenges is, however, not lost on community leaders. Early last year, the city committed $40 million to fund affordable housing, projects like the 28-unit Richer Place Apartments in Kimball Junction, which opened last September, and a mixed-income housing plan as part of the proposed redevelopment of Bonanza Park, a 100-acre neighborhood bound by Park Avenue and Kearns Boulevard. Scott Loomis, director of the Mountainlands Community Housing Trust, says that despite the current scarcity of affordable housing—fed by the addition of 1,000 to 1,500 new jobs every year—he’s more optimistic than ever. “I’ve been doing this for over 15 years, and I’ve never felt more encouraged by getting affordable housing projects done than I am now,” Loomis says. “There’s lots of projects in the works—including some things we’re working on—that could make a substantial difference.”

A joint task force of Park City and Summit County commissioners is also working on a 30-year plan to boost public transit and decrease the number of single-commuter vehicles throughout the county. And in November, Park City voters approved a $25-million-dollar bond to acquire and preserve Bonanza Flats, a 1,400-acre area of undeveloped land south of Park City, if and when the property becomes available.

For his part, Mayor Jack Thomas is convinced Park City can—and will—maintain its small-town spirit by embracing the uniqueness that has defined it since its inception. Thomas points to a strong public transportation system and more affordable housing as solutions that will keep a cross-section of people living, working, and investing in the town. “We’re a small hamlet in the mountains, and we’ve got to keep that as part of our core vision for the community. We have a small-town sense of community and historic character within a natural setting. Those qualities will still be here in 20 years.”