Peek Inside 3 Local Artists' Studios

For many artists, the studio is a room embedded with a meaning much deeper than other interior spaces. It’s a place where the creator can freely conjure new concepts, forms, and styles and be judged only by herself. Here we provide a voyeuristic glimpse into the workplaces of three local artists, giving us a sense of not only where and what each creates, but also who they are.

John Helton

Building large-scale sculptures requires heavy-duty tools and plenty of room. Artist John Helton lives in Park City but has worked out of an airy, industrial building in Oakley for the past 25 years. His studio is bright with bay doors and high ceilings—the perfect setting for him to create his sizable bronze sculptures.

John Helton in his Oakley studio.

Image: Sandra Salvas

Helton grew up in New York City, where he came by his penchant for art honestly. His father was also an artist who frequently took his young son to galleries and museums. Helton graduated from the Parsons School of Design and has worked in multiple mediums, including painting, writing, wood sculpture, and furniture design. “I’m always exploring the potential of new materials,” says Helton, though bronze stands out as his medium of choice. “I love the beauty of constructed bronze, its smooth texture and lines,” he explains. “It allows me to create something with an elegance and grace I haven’t realized in other mediums.”

The primary purpose of Helton’s workspace is to facilitate problem-solving and design, as the actual bronze pieces are ultimately cast in foundries. Eighty percent of the work on his sculptures is preparatory; he meticulously engineers the structures in cardboard and wood before final fabrication off-site.

These working models cover the large tables in Helton’s studio, helping him determine composition and scale and serving as a continuous source of inspiration. Helton explains that he is constantly seeking “different ways of looking” and studying the scraps of materials he intentionally leaves around the workshop. He sometimes plays with ideas for years while he actively produces new pieces.

Sculpture in John Helton's studio.

Image: Sandra Salvas

Helton’s finished sculptures, available locally at Julie Nester Gallery (1280 Iron Horse Dr, 435.649.4893), are meant to bring form to scientific concepts, serving as metaphors for the unseen interaction of space and time, the artist explains. Characterized by sweeping curves and intersecting lines, Helton’s work does indeed evoke a sense of motion while highlighting line as well as form. They seem to be studies of the patterns evident in the rhythm and balance of life.

“Bronze is a real commitment,” Helton says. “You really have to believe in what you’re doing and have a clear vision.”

Jenny Terry

Classically trained as an oil painter at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, Jenny Terry has been painting since childhood. But, as a busy mother, it hasn’t always been easy to focus on her passion. It took surviving cancer to put her life into sharp perspective, and in the 12 years since, she has been steadily pursuing the art-centered life she’s always wanted.

Terry’s studio space is tucked away in her basement, making it convenient for her to work while tending to the tasks of everyday life. Her adaptation of a small, personal space shows the determination and inventiveness artists often apply to pursue their calling.

One of Jenny's paintings.

Image: Sandra Salvas

“Every person’s studio is so different,” she says. “Mine is functional.” For the past five years, she has been focused on encaustic painting, an ancient method of applying beeswax mixed with pigment to a prepared surface, usually heated wood. Encaustic isn’t the easiest medium to work with, but, as Terry explains, “Every time I went into a gallery and saw a painting that made my knees buckle, it was encaustic. It rocked my world.” Once she began learning the medium and finding novel modes of expression, there was no turning back.

Her home studio in Jeremy Ranch is a laboratory for encaustic experimentation. Terry works surrounded by ingredients to make and manipulate her medium: blocks of pigmented beeswax, pans to melt down damar resin (used to harden the wax), brushes, scraping implements, and small pots of the finished medium that sit on a heated surface while the artist works.

Encaustic is often noted for its smooth, glassy texture and subtle layered quality. Terry’s paintings, however, are heavily textured, mixed-media creations made with a technique that involves allowing the wax to cool in layers at varying rates, then marking the wax with custom-made stamps, and finally embedding it with small objects she collects and stores in stacked drawers. Her colorful scenes of nature and Park City landmarks are punctuated by the unexpected—coins, seeds, beads, paper, natural fibers, etc.—which give them a playful, engaging feel.

Terry’s uncommon approach to her work has paid off in recent years. She’s had a booth at the Park City Kimball Arts Festival, and full-size prints of her work can be found at Peak Art & Frame (6541 Landmark Dr, 435.649.0801). Terry looks at the process as she would “any small business,” saying the key is to “experiment and keep moving forward.”

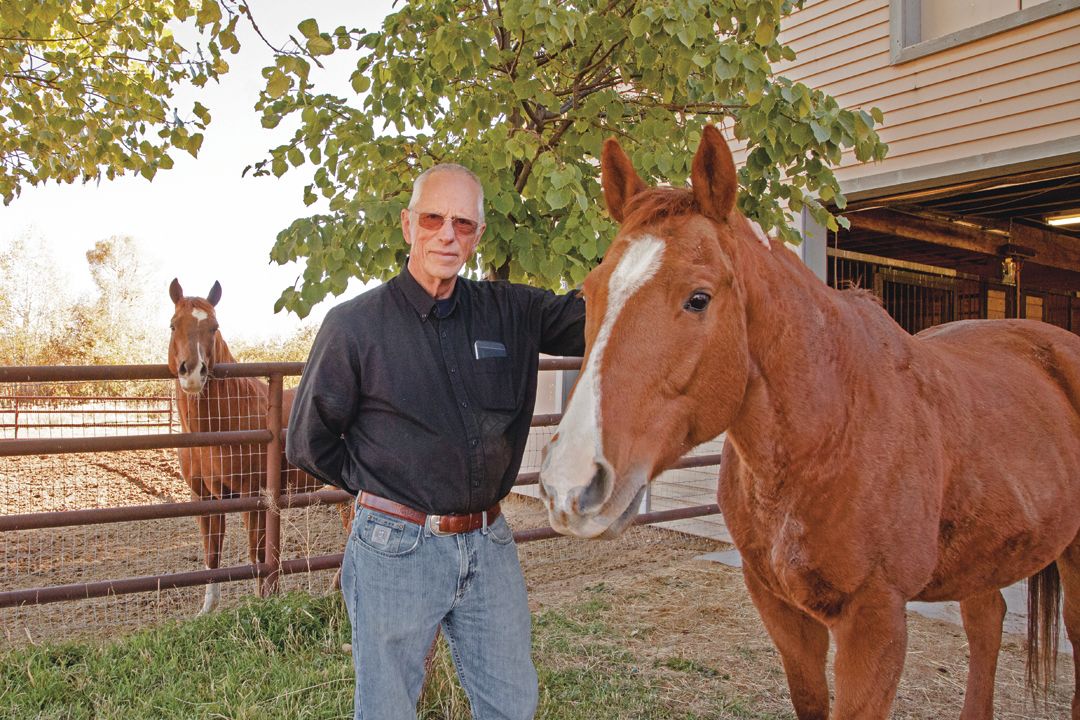

Weller gives a pat to one of his muses, All Right Starlight.

Image: Sandra Salvas

Don Weller

At 79, Western watercolorist Don Weller says, “I’m getting old, but I can’t retire. Painting is what gets me up in the morning. If I’m not riding horses or skiing, I am painting, with few exceptions.”

Outside Weller’s two-story studio, located on his and his wife Cha Cha’s 10-acre ranch in Oakley, is his inspiration: horses, a herd of Aberdeen Angus cows, a bull, and sometimes buffalo. Weller describes his work area as “just a space with a little north light. Because artists always want to brag about a studio with north light. But now paintings are seen under artificial light in gallery settings, so it’s actually best to paint under artificial light.”

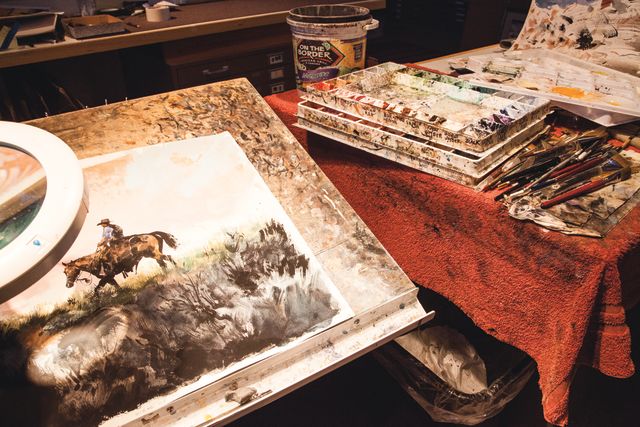

Before taking up painting full time, Weller was a graphic designer and worked on a variety of projects, including Park City Magazine.

Image: Sandra Salvas

The studio walls are covered in family photographs and momentos. There’s a picture of Weller and Cha Cha getting married in Japan 40 years ago; postage stamps, Olympic posters, and wine labels Weller has designed; and salt lick “sculptures” his animals have made, “one by a herd of goats, another by a horse named Little Pete,” Weller says.

It’s here that Weller composes his watercolors of cowboys and cowgirls at work, horses and red rock landscapes, and sagebrush hills. “Getting lost in my work is addictive,” he muses. “When I’m in my studio painting and lost in the process, I’m back on the rocks in Moab herding cattle.”

Weller’s work can be found at galleries throughout the West, including in Park City at Montgomery Lee Fine Art (608 Main St, 435.655.3264, montgomeryleefineart.com).

Image: Sandra Salvas

Draped over the railing on the upper level of his studio is a flag; one side green, the other, red. When Weller wishes not to be interrupted, he drapes the flag over the railing red side up. “There’s a point in painting when it’s drawn and planned and then you’re putting in colors, and while I’m painting the flanks of the horse I’m thinking about how that color will influence the color behind the horse or on the guy’s chaps, and there are lots of decisions going on in my mind a little bit ahead of my hand actually doing this stuff. And then your wife comes in and says, ‘honey, did you buy some Kleenex?’ That’s when I flip it to the red side. And it does absolutely no good because Cha Cha doesn’t even look at it. Sometimes I like an interruption, though. So then I can flip the flag to green. But it’s best if it’s on red.”