From Silver to Gold: A History of Park City Skiing

The gondola at Park City Ski Area (now PCMR) was once the world’s longest.

Sometime this winter, take a ride on Park City Mountain Resort’s Town Lift. After you get off at the top, pause for a moment and consider mountain time in 50-year increments. You’re standing in the gap dividing the resort’s lower mountain from its upper ridgelines; resist the temptation to look up. Instead, look down the hillside and visualize the passage of two 50-year eras along with this season, the start of a third.

Below you lie the ruins of the Silver King Mine, which, a century ago, teemed with men and machinery working at the peak of Park City’s mining era. Then look ahead in the same gap to the oddly angled, green-sided, open-ended building sitting abandoned above the Bonanza chairlift. Fifty years ago, it signaled a new era. Now slide down the run in front of you to the Bonanza chairlift, and slip into the present as you board the six-passenger, high-speed lift.

The Silver King Mine—with its remnant of a hoist building sided in corrugated metal, its concrete change house, and the crumbling crushing mill farther down-

canyon—reminds us that Park City was never meant to be a ski town, never designed from the ground up with condos and faux Euro village streets. Park City a century ago was at its zenith as a blue-collar mining town. Drawn by the site’s status as the second-largest silver strike on the continent, unskilled immigrants jumped off railcars at the base of Main Street and walked to the mines to find work. No one built fancy houses; it was a transient place, never meant to last, say, 50 years.

The last gasp of prosperity in that first era dwindled in the 1920s, and the Great Depression pretty much finished off the old Silver King and its companion mines. By 1957, Park City seemed finished. “But there were 1,100 of us live ghosts still here,” the mayor of that time, Will Sullivan, recalled to me one day in his Park Avenue kitchen.

The Silver King Mine.

One remaining mine company consolidated what had once been hundreds of individual mines, determined, along with town leaders, to keep Park City alive. For years, they’d seen lifelong friends simply walk away from their worthless old miners’ shacks above Main Street, abandoning them to be pilfered and vandalized by the town’s few remaining adolescents. As it happens, these were the same kids who also played at Snow Park, the tiny two-lift, hand-built ski area over in Deer Valley that was open on weekends for a buck and a half, ski lesson included. An occasional ski train even chugged up from Salt Lake City, dropping off skiers on a Saturday for a day of play.

That last remaining mine company took notice. In secret, its leaders planned, consulted bankers, and applied for a government economic stimulus loan meant for depressed rural communities. They still wanted to mine silver ore, but they figured they might also make money on the hills above the tunnels and shafts.

The late Jim Santy, a music teacher with a side business as a surveyor, loved to tell of the day the mine company asked him to survey for a gondola. “A gondola?” he questioned, with visions of Venice. “What a crazy idea—where will they get the water?”

The federal loan languished in bureaucracy, but by lucky happenstance, Jack Gallivan, then publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune, was an old political pal of John F. Kennedy. He was also a Park City native, born and raised, and his uncle used to own the Silver King Mine. When Gallivan was invited to lunch with the president at the White House one day, he mentioned the stalled loan. It got unstuck soon thereafter.

Treasure Mountains Ski Area opens in 1963.

With the $1.25 million Area Redevelopment Loan secured, the 1962 and 1963 construction seasons were furiously paced. Out-of-work miners had jobs again, this time aboveground. A German engineer arrived to supervise construction of the gondola—to glide through the air, not through the water. “He didn’t speak much English, and none of us spoke German,” mine shop foreman Bob Birkbeck recalled, “but he drew pictures, and we could pretty much figure out what he wanted.” Together, miners and the imported engineer built the longest gondola in the world, and the only one with a turn in it. Inside the angled green building with the open ends, gondola cars were switched from one cable wire to another in the Angle Station—really two separate gondola systems with a connecting mechanism.

Somehow it all got built 50 years ago, in time to open for the 1963–64 ski season. The mine company called it Treasure Mountains Ski Area, ran it for several years, and sold it at a loss to an Aspen developer named Edgar Stern. Stern attempted to make the fledgling ski area profitable, borrowing to build condominiums, and he brought in his good friend and Aspen neighbor, Stein Eriksen, to promote skiing.

A bad economy forced Stern to sell the resort—renamed Park City Ski Area—in 1975. “I was looking for something for my son and I to do together,” businessman Nick Badami told me long ago. His son Craig was crazy about skiing, and New Yorker Badami was bored with retirement, so he bought out Stern and went into the ski business. Under the Badamis, Park City Ski Area grew from struggling start-up to successful megaresort. Craig’s promotional zeal attracted World Cup races, putting Park City on the international stage. Eriksen—known to everyone simply as Stein—stuck around, too, lending elegance to the slopes, and his once-a-day somersault on skis helped usher in the sport of freestyle.

Left to right: 1983 World Cup Champion Tamara McKinney, Park City Ski Area Marketing Director Craig Badami (killed in a 1989 helicopter crash), and former US Ski Team racers Tori Pillinger and Eva Twardokens

Eventually the International Olympic Committee took notice, and Park City Mountain Resort hosted all snowboarding events and the alpine giant slalom and slalom competitions during the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. Craig Badami never lived to see the Olympics on his own mountain. When he died in a helicopter crash at the resort after the 1989 World Cup, his father looked for another family to carry on their vision. In 1993, the Cumming family of Salt Lake City assumed ownership, and they continue to this day to build on a half-century legacy.

Turbulence creates the weather that blesses the Park City slopes with 365 inches of snow on average each winter. Figuratively, that term also describes the modern ski business: who knows where the next half century will take the resort?

As a nearly 50-year skier, I know one thing. The most perfect day of my ski life involved patiently waiting for Ski Patrol to finish avalanche control work in Park City Mountain Resort’s highest reaches, Jupiter Peak. The wait resulted in my chance to stand alone at the top of Portuguese Gap, with maybe 36 inches of pristine Wasatch powder lying in wait below me. No one else had that moment that day. Without any witnesses to dispute it, I’ll say every turn I made was as elegant as Stein’s always are.

Most of us get to live through one 50-year era. Few see two such time periods. I won’t be around in 50 years to see what happens to the mountain I and so many others love, but I know someone, 50 years from now, will stand alone atop Portuguese Gap and encounter the pure bliss of the perfect run.

Time Traveler

A Park City Mountain Resort timeline

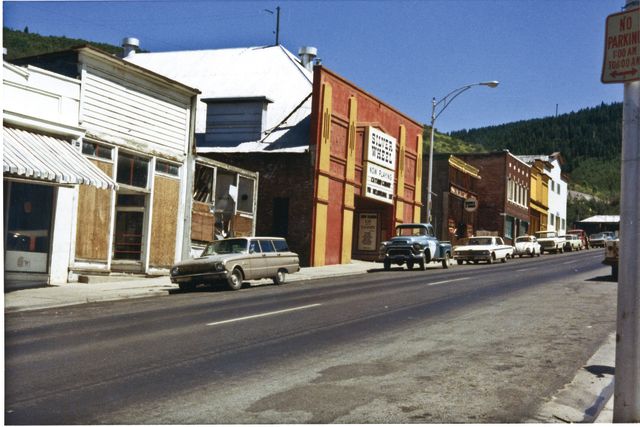

Main Street

1951

Park City is listed in the book Ghost Towns of the West. Remaining Parkites are indignant.

1962

The US Commerce Department grants Park City a $1,232,000 Area Redevelopment Loan to build a ski area.

1963

Treasure Mountains Ski Area opens for business.

Stein Eriksen

1971

Edgar Stern purchases Treasure Mountains Ski Area, renames it Park City Ski Area and recruits Stein Eriksen as its celebrity skier.

1974

The US Ski Team relocates its headquarters from Denver to Park City, moving into training facilities at Park City Ski Area.

1975

Nick Badami buys out Stern and institutes an upgrade of lifts, terrain expansion, and snowmaking.

Tamara McKinney

1985

The first FIS World Cup held at Park City Ski Area.

1989

Craig Badami is killed in a helicopter crash after 1989 World Cup race.

1992

Nick Badami sells an 80 percent interest to the Cumming family of Salt Lake City.

1996

Snowboarding is allowed, and the resort changes its name to Park City Mountain Resort.

2002

PCMR hosts the Winter Olympics’ snowboarding and slalom and GS skiing events.

2006

Silver Star Lift and alpine coaster open.

Mid Mountain Lodge

2009

Once a miners’ boarding house and at another time housing for US Ski Team athletes, the newly remodeled Mid Mountain Lodge restaurant reopens.

2012

PCMR files suit against Talisker Mountain Inc. (owner of much of the land on which PCMR operates) over a lease dispute.

2013

May: Talisker transfers control of the land on which PCMR operates to Vail Resorts. August: Vail Resorts files an eviction notice demanding PCMR vacate Vail Resorts’ managed ski terrain. As of press time: Litigation between PCMR and Vail Resorts over lease extensions continues.