The Center of Everything

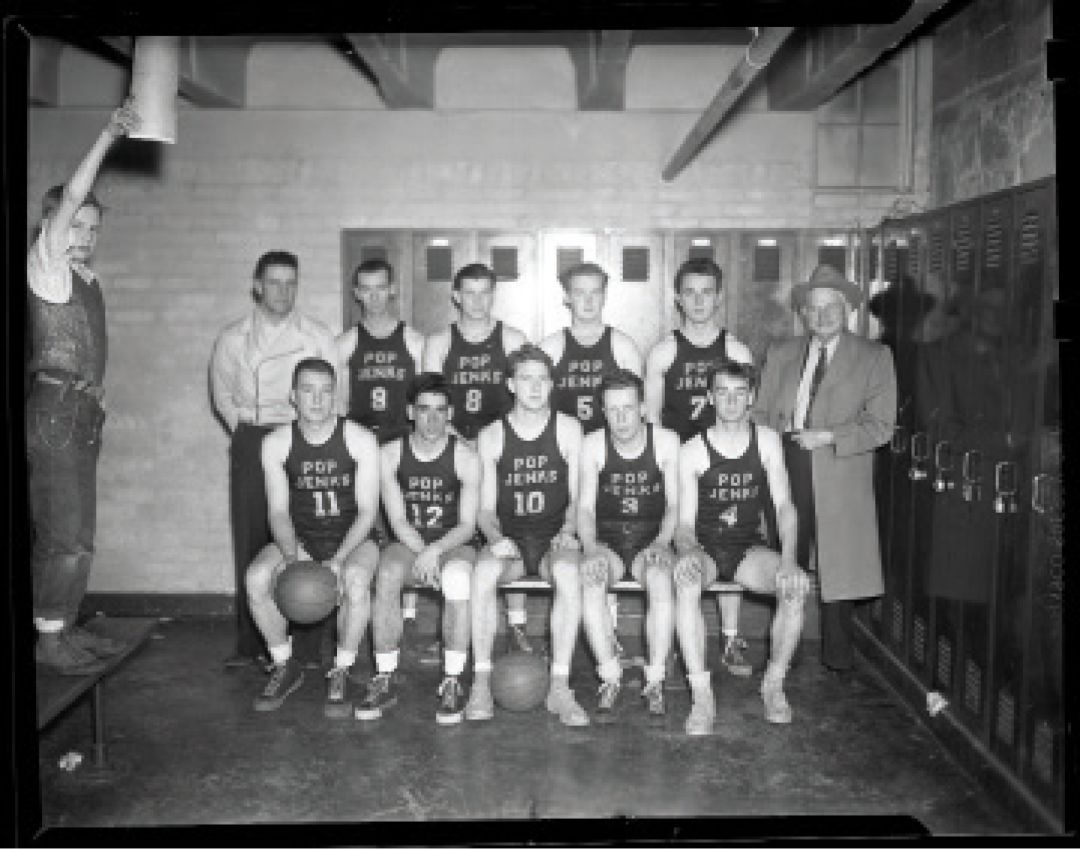

Image: Park City Museum

Before conference rooms, country clubs, or rec centers, there was only one place in Park City where people gathered to celebrate, mourn, exercise, and politicize: the War Veterans Memorial Building. For almost 50 years, this one building, located at 427 Main Street (now home to Park City Live), was, for all intents and purposes, the center of everything.

In 1919, Park City’s American Legion proposed a World War I veterans memorial. But instead of a monument or statue, the legionnaires wanted to erect a building to serve as a home to culture, recreation, and political thought. For years their efforts failed for lack of funds. But then in the 1930s, three events came together to make the Memorial Building possible: Ed McPolin, a charismatic local and strong Memorial Building supporter, was elected as a Summit County Commissioner; a new state law allowed counties to levy a tax for war memorials; and President Roosevelt’s New Deal Public Works Administration program allowed grants for civic projects. Park City, passed over for the county seat and hospital, argued for the equity the Memorial Building would bring. In 1937, with a vocal crowd of eastern county protesters in attendance, the county commission approved the Memorial Building for Park City.

The county purchased the 1880s-era Blyth-Fargo store site on Main Street and, with a budget of $127,500, hired nationally renowned Utah architect Raymond Ashton. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Ashton designed a building unlike any in Park City before or since. Its imposing size and modern design stood in stark contrast to the diminutive storefronts surrounding it. Called PWA Moderne, the style was monumental in scale with a symmetrical façade, smooth concrete surfaces, and a framed entrance. Panels above the doors were ornamented with art deco floral motifs. The design was meant to express the new age of science, technology, and the machine.

The Park Record noted with great fanfare every truckload of lumber, steel, and “hundreds of sacks of lime” that arrived at the site. “The skeleton of the Memorial Building is now assuming gigantic proportions,” the newspaper marveled. As work proceeded, a copper box filled with documents was encased in the cornerstone. A crowd watched as coins were added before it was sealed. When the building was completed, legionnaires laid sod, and the Women’s Athenaeum donated a grand piano. A Main Street beautification campaign was launched to spruce up neighbors that looked shabby next to the sleek newcomer.

Image: Park City Museum

Dedication day (January 20, 1940) was attended by more than 600 people from throughout northeastern Utah. Bugles sounded, a plaque bearing the names of Summit County veterans was unveiled, and Governor Henry Blood led dignitaries in praising the building. The crowd poured into all 50 rooms, which included an auditorium/gymnasium, a ladies’ lounge, a banquet room with a state-of-the-art adjoining kitchen, an office and apartment for a live-in manager, a rifle range, four bowling alleys, a poolroom, and an area with dirt floors that became known as The Catacombs.

A Legion spokesman proclaimed, “The completed building stands as a memorial and a monument to beauty.” The town was bursting with pride, and everyone clambered to schedule an event at the new venue. The Rifle Club announced an indoor shoot, the Athenaeum planned a candy pull in the kitchen, and a model airplane class held a flying contest in the gym. The Record reminded everyone to “take off your hat in the building, since it is a memorial.”

During the 1940s and 1950s, the building was a beehive of activity. Dances were held nearly every week, with bands like the Melody Makers drawing in crowds. It became the place for weddings, funerals, bridal showers, reunions, and anniversary parties. There were classes of all kinds, from upholstery to tap dancing, and a constant schedule of movies, bingo parties, carnivals, rummage sales, talent shows, and fundraisers. Meeting rooms were packed nightly with club and fraternal organization gatherings. First aid classes for miners and well-baby clinics were held, typhoid shots were dispensed, and there was a demonstration of the iron lung purchased for Miners Hospital.

With the advent of World War II, the Memorial Building hosted registration for the 1940 draft, drives for war bonds, “Salvage for Victory” campaigns, and the distribution of gas ration books. The building was the site of county political conventions and the place to host visiting dignitaries. The state held 1947 centennial festivities in the gym and conducted gun safety programs at the rifle range.

The building “has become the place for gab fests and chewing the rag,” observed the Record. Everyone congregated there to see and be seen. But heavy use took its toll, and the city and county fought an ongoing battle for funds. During the 1950s, as Park City’s population plummeted, it became an important gathering place to hold the town together. It also became a place of refuge in times of need, such as when a landslide in Empire Canyon forced residents to seek safety there.

The Memorial Building’s condition continued to decline through the ’60s and ’70s, and people complained about its ugly, outdated exterior. Grants were applied for and rejected, volunteers helped with repairs, and the county formed yet another governing committee. A county commissioner, fed up with complaints, said, “I would be in favor of locking the doors.” Finally, after years of bickering, the county turned the building over to the city in 1977.

The police and recreation departments moved in from overflowing city hall across the street as a citizens group protested, fearing community use of the Memorial Building would be shoved aside. The building and planning department, justice court, and city council soon moved in as well. Community Wireless started a radio station in the windowless projection booth, dubbed the “broadcast bunker,” and the US Film Festival (precursor to the Sundance Film Festival) set up headquarters. Belly dancing classes and solar energy workshops were full, novice climbers learned to lower themselves over the roof, and an actors ensemble presented plays on the stage.

A decade later, the city moved to the Marsac School and purchased the Carl Winters School Building (now the Park City Library) and the Racquet Club. The Memorial Building, with renovations estimated at $2 million, was ready for its next chapter. The once applauded, and later reviled, architecture was accepted as part of the historic timeline of Main Street. But in 1986 the city sold the building to a developer for $500,000. Businesses occupying the Memorial Building after then included Z Place, Harry O’s, and now, of course, Park City Live. The plaques and veterans’ memorabilia were brought to the county courthouse for safekeeping, and the place well-known local Bea Kummer called “the busiest in town” was no longer where Parkites gathered to be a community.